History can help re-frame California’s current rent control debate

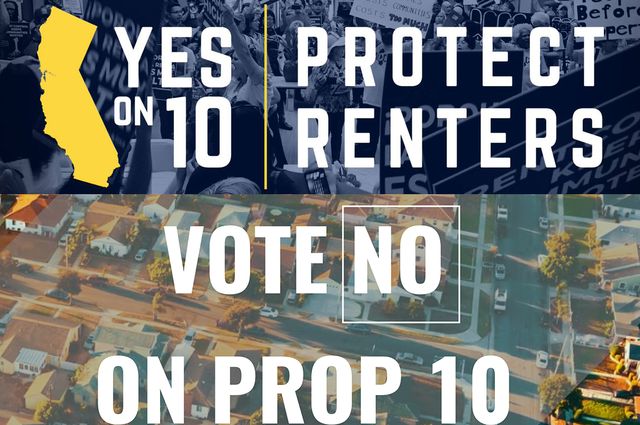

In less than two weeks, as the nation heads to the polls after a contentious mid-term election season, California voters will cast their votes on Proposition 10. The hotly debated measure would repeal the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, which froze municipal rent control laws across California and made them a matter of state, rather than local, governance. A repeal would once again allow cities to decide whether to expand rent control. Tenants’ rights and eviction defense groups view Prop. 10 as a much-needed step to address the affordable housing crisis while real estate and property-owner advocates have largely opposed it.

On Oct. 16, spurred on by the release of its first white paper — titled “People Simply Can’t Afford to Pay the Rent” (PDF) — the UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy welcomed community leaders to campus to discuss Prop. 10 as part of UCLA’s ongoing “Why History Matters” discussion series.

“We invite people to understand the history of the issue as essential prerequisite to their civic and electoral engagement,” said David Myers, director of the center and the Sady and Ludwig Kahn Professor of Jewish History at UCLA.

Panelists ranged from cautiously hopeful to cautiously dubious about Prop. 10’s chances of passing, noting that it will likely take record-high voter turnout to approve it.

Lead author of the Luskin paper, Alisa Belinkoff Katz, set the stage for the evening with a history lesson, recounting two other times when Los Angeles experienced acute housing shortages. During World War II a flood of much-needed workers for the defense industry pressurized housing demand, so rent control laws were put in place to prevent price gouging. Such laws were even promoted as patriotic. Those policies ended in 1950, Katz explained.

In the last half of the 1970s, residential property values in Los Angeles shot up 69 percent countywide, causing financial pain to homeowners and renters. That resulted in property tax reform by way of Proposition 13 in 1978, and eventually led to the current rent stabilization ordinance. This law, which only affects buildings constructed before 1979 and excludes single-family home rentals, limits rent increases to the prior year’s inflation and ultimately allows landowners to raise rents to market levels when tenants move.

Nevertheless, the 69 percent increase in home prices that spurred Proposition 13 had, by the end of 2017, become a 238 percent increase in home prices adjusted for inflation, according to the paper. Ever-increasing property values are once again leading to higher rents. This combined with an increase in poverty and a decrease in affordable rental units has created the current crisis and contributed to the county’s 53,000 homeless. The report estimates the median renter in Los Angeles pays an untenable 47 percent of their income in rent.

The state’s Costa-Hawkins Act of 1995, which Proposition 10 would repeal, prohibits municipalities from implementing additional rent control measures.

Elena Popp, executive director of the Eviction Defense Network graduated from UCLA in 1985 and immediately went to work focusing on efforts to house the homeless.

“Here I am, almost 60, should be thinking about maybe retiring and we’re back at this,” Popp said. “I’m at the same place I was in 1980s with one horrifying story after another coming through my office — like a 69-year-old woman getting hit with a $1,000 per month increase from a 42-year tenancy and her monthly income is only $866. She will be homeless. Hence the fire in the belly gets lit again.”

Working class and minority residents especially are being displaced into the streets, which should concern homeowners who want to protect property values, said Popp, who is a Prop. 10 supporter. She and other supporters have been trying to educate voters and counter the nearly $68 million opponents of the measure have poured into the election cycle.

“Every time I say something to someone about rent control, they say ‘that’s not a solution to the housing crisis,” said Marques Vestal, a UCLA Ph.D. candidate in history, who provided research for the paper. “I tell them, ‘I didn’t say it was a solution, it’s a response.’”

Vestal said he thinks about the issue metaphorically. World War II constituted what could be viewed as an acute crisis, caused by war time, while the issues of the 1970s were more like a chronic condition.

“Let’s think about that in terms of a patient, you have one with an acute injury like a gunshot and the other one with a heart attack caused by a chronic disease,” he said, “In either case, it’s an emergency. We’re not going to sit there when a paramedic starts to triage the emergency and say ‘that’s not a long-term strategy.’ No. You have to plug the wound; you have to resuscitate your patient. That’s the nature of emergencies. And what this paper does is allow people to re-frame the issue properly.”

There’s also a philosophical element about the notion of “home” at play, Vestal reminded the audience. Is a person’s presence within a community only of value to that community if they can afford to pay high rents? If a person has always known a place as home, should they be expected to leave that home if they have not managed to acquire wealth in the city?

In a city like Los Angeles, with a mere 3 percent vacancy rate for apartments, there is widespread agreement that more development is crucial, but even the most optimistic projections say it could take a decade to make a dent in that need, said state Assemblyman Richard Bloom.

“We need 2.5 million units and we need to build them by 2025 and we should be building 3.5 million,” Bloom said. “But we are only on track to build 1.5 million, so we are going backwards.”

In the meantime, it’s not just the poor who are getting crushed in the crisis, he acknowledged, but middle class families, teachers who are critical to communities and millennials.

“We can’t simply write them off and say this is a lost generation who will not have housing or who will have a lower quality of life,” Bloom said. “That’s the main reason I took on the Costa-Hawkins debate in the first place.”

Bloom was the first lawmaker to introduce legislation that would revise or repeal Costa-Hawkins. It died in committee. Bloom noted that he thinks legislation would lead to a better solution than the one-size fits all nature of a ballot measure.

William Witte, chairman and CEO of Related California, a multi-family and mixed use development company that is currently working with the city to build 900 units of affordable housing for veterans, said he’s not convinced Prop. 10 is the answer.

“But you can’t write off what’s happening to people,” Witte said.

What also needs to be in the mix is how California cities and the state work with developers to approve projects.

“It takes eight to 15 months to get a project approved in Seattle, a city of major growth, gentrification and everything that comes with that,” Witte said. “In California, it can take three years. Ever try building in West L.A.? Good luck.”

As much as they may complain about regulations, developers do like it when the rules are clearly spelled out, Witte said. They like to know what the city wants and expects and then they can go make a plan to acquire backers and funding that will allow them to make a profit within those confines.

Originally posted in UCLA Newsroom: Source