Ellen DuBois observes that expanding the vote is still not something established political leaders are eager to do. (Photo Credit: Scarlett Freund)

They persisted.

August 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which ensured that all American women could vote in federal elections. Ellen DuBois, UCLA professor emerita of history, has devoted her academic life to the stories of the women (and men) whose unrelenting, passionate and organized advocacy withstood 75 years of shifting partisan politics to finally enfranchise women in the U.S.

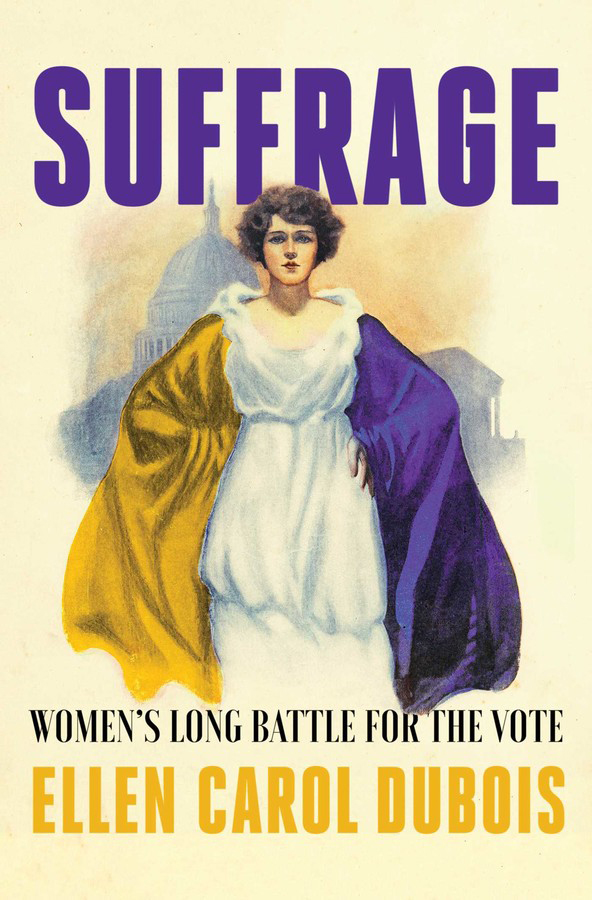

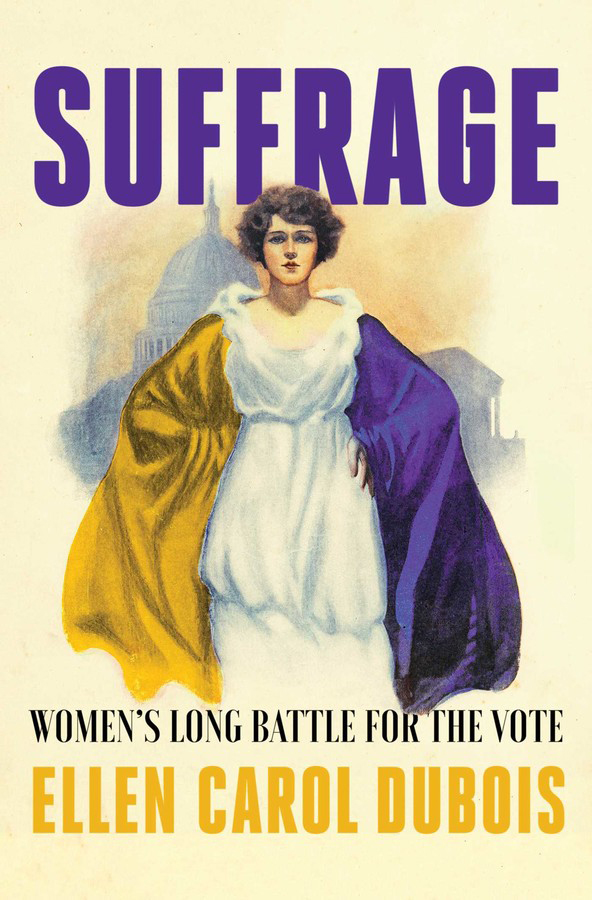

Written for anyone who cares about rights in America, her latest book, “Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote,” which came out Feb. 25, takes a comprehensive look at the incomparable effort.

Her storytelling illuminates the lives and efforts of three generations of suffragists, as her prose passes the baton from woman to woman, grandmother to mother, mother to child. She celebrates the efforts of such champions as Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul, who were critical in the final push into the 20th century, and she illustrates how African American women — led by Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Church Terrell and Mary Ann Shadd Cary — demanded voting rights, even when white suffragists ignored them.

In a presidential election year, and as primary voters head to the polls for Super Tuesday on March 3, it is fitting to heed activist Gloria Steinem’s praise for DuBois’ work:

“Ellen DuBois tells us the long drama of women’s fight for the vote, without privileging polite lobbying over radical disobedience — or vice versa. In so doing, she gives us a full range of tactics now, and also the understanding that failing to vote is a betrayal of our foremothers and ourselves.”

We asked DuBois to share some of the key takeaways from “Suffrage.”

The Americans who took up the fight for women’s right to vote were originally proponents of “universal suffrage,” which would have meant a constitutional amendment affirming votes for every American citizen over the age of 18 — regardless of race or gender. How different might this battle have been if that original purpose had been successful?

The Constitution gives little control to the federal government over voting — just times, places, etc. — and none whatsoever over who gets to vote. The three voting amendments, including the 19th, barely tamper with that, only forbidding the states from named disenfranchisement. And as we know from the history of African American voter suppression, those are easy to get around.

If the suffragists’ early attempt to reframe voting as a positive right of national citizenship [had been successful], much of what we suffer today by way of voter suppression — which comes from the states — would no longer be legal or constitutional. We would have universal enfranchisement, which we cannot say we have now.

“Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote” Photo Credit: Simon & Schuster

This book is also a fascinating rendering of the kaleidoscopic nature of American partisan politics. What was the biggest obstacle to women’s suffrage?

This is a question that suffragists and historians have long pondered. General male opposition to women taking a place in politics, as well as women’s hesitation about leaving their traditional roles, certainly played a part.

But as I studied the last few decades of the movement, I was especially struck by the determination of politicians to keep women without votes — both at the national level, fighting against amendment passage, and the state level, opposing ratification, the ultimate obstacle.

This was the case even when it was clear to the final opponents that women’s suffrage was inevitable. Politicians’ opposition certainly reflected their own conservative ideas about who women were — their delicate wives and the pesky radicals who wanted the vote — but it was also a political calculation. The suffragists and other social activist women had developed a solid reputation as nonpartisan reformers, and politicians didn’t want that. Finally, it was impossible to predict which party enfranchised women would favor. It turned out to be both.

As we know from our own times, expanding the vote is still not something established political leaders are eager to do.

By the time the 19th Amendment was passed, millions of women already had the right to vote in federal elections, thanks to state constitutions. By 1919, women in Wyoming and Colorado had voted in five or six presidential elections. Western states like California were critical to eventual nationwide suffrage. Who were some of the most important suffragists who helped win the vote in California?

California, when it amended its state constitution to enfranchise women in 1911, was the sixth state to do so — and by far the most important.

Maud Younger was a wealthy San Franciscan, among those young people known as “new women” for their eagerness for modern lives and new experiences. She left home, went to New York City, worked as a waitress and trade union activist, and returned to California to organize working women. They called her the “millionaire waitress.” She was responsible for getting the brewers union on board, which helped to overcome suffragists’ reputation for being anti-alcohol.

Sarah Massey Overton, an African American woman from San Jose, not only organized her area’s African American community, but — unusual for these years — worked closely with white suffragists in the interracial Political Equality League.

Hispanic Californian suffragists were harder to trace. I located a very interesting woman, Maria de Lopez, whose family was in California before its statehood. As of 1910, she was a college graduate and taught at UCLA and later was a scholar of Spanish-language literature. Fascinating!

Multiple other amendments to the U.S. Constitution were ratified before the 19th. How did the push for these amendments affect the fight for women’s suffrage? Why was the 17th Amendment critical to the eventual passage and ratification of the 19th?

The reconstruction amendments 14th and 15th were crucial: the latter for omitting women from the expansion of the franchise, which angered suffragists; the former for establishing — for the first time — national citizenship, which led hundreds of suffragists to claim the right to vote in the 1870s including Susan B. Anthony.

It was several decades before other amendments were added. The 17th made the election of senators dependent on the people’s vote, when previously they were appointed by state legislators. This played a role in breaking the final opposition to the women’s suffrage amendment in the upper house. The 18th Amendment [prohibition of alcohol] took this contentious issue, often associated with women voters, off the table and removed an issue of the opposition.

Do you have a favorite suffragist? If so, who and why?

I’m often asked this. I do love Elizabeth Cady Stanton for her brilliant insights into the multifaceted nature of women’s subordination and her vision for broad freedoms for women. These days she is remembered more for her racist and elitist outbursts against men who voted before women, but I think she has more to offer us than just that. These women are all so great, so varied, so brave, so determined — “nevertheless they persisted.” I love them all.

Your book also illustrates the power of an archive. Susan B. Anthony had the brilliant foresight to establish a multivolume history of the movement — including photographs and images of suffragists — and then donated copies to libraries and universities for posterity. Obviously this was critically important to historians like yourself and Eleanor Flexner, who wrote 1959’s “Century of Struggle.” What other stories are waiting to be told from this archive? What are you working on next?

The suffrage movement is unique for its geographical breadth and depth. It lasted so long, and constitutional amendments, which are contested like this one, require organized activism in virtually every state. There is so much more to be said about suffragists in our country.

A second issue is a more complex one: the varied and painful history of racism within the suffrage movement, which lasted from the years of emancipation through the height of the Jim Crow era.

Finally, and this is one of my unfinished projects, women’s enfranchisement was an international issue. In almost every country where women have received the right to vote, they have organized to fight for it. It was rarely given. I’m working on that in the interwar years.

My next big project is a major biography of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who has never really had one. I’m going to give her that.

DuBois is on a speaking tour for the book, including several upcoming events in town.

March 7 at 2 p.m. — “The Surprising Road to Woman Suffrage” illustrated book lecture at Los Angeles Public Library’s Central Library

March 8 at 1 p.m. — “The Right to Vote Then and Now” panel discussion at Royce Hall. Also featuring Adam Winkler, Brenda Stevenson, Katherine Marino, Sheila Kuehl and Sandy Banks.

March 14 at 11 a.m. — “The Surprising Road to Woman Suffrage” Caughey Foundation Lecture at the Autry Museum of the American West

March 15 at 2 p.m. — Book presentation with Jessica Millward, UC Irvine associate professor of history, and Culver City Mayor Meghan Sahli-Wells at the Wende Museum

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.