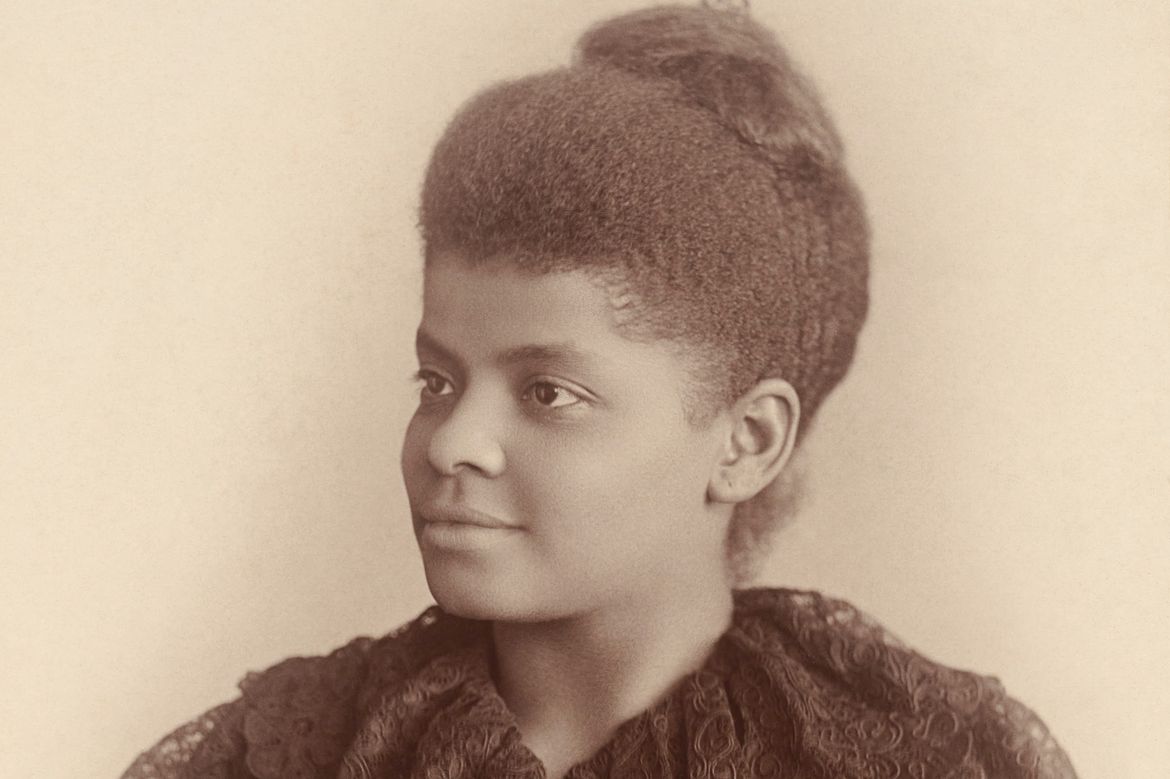

From left: Riya Patel, Mayte Ipatzi and Michelle Cervantes, all seniors and part of the first cohort of labor studies graduates at UCLA. (Photo Credit: Joey Caroni/UCLA)

The class of 2020 is stepping out of their UCLA studies into a world that is crying out for massive social change and racial justice amid an economic recession that is disproportionately affecting communities of color.

While for many people around the country this feels unprecedented, for UCLA’s first cohort of graduates to earn degrees in labor studies, an interdisciplinary major run by the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, this is much like every other health or economic crisis they’ve studied.

They’ve spent the last few years learning about workers’ rights, wage theft, peaceful protest, labor organizing and issues of race, class and gender in the workplace. They’ve conducted research that interrogates the very institution they’ve been studying within.

They are curious, passionate about community building and cautiously hopeful about what is a decidedly murky near future.

They’ve spent the last months of their college experience physically separated from the community they have built, but remain committed to forging connections, and forging ahead.

Riya Patel started out majoring in economics, a subject she fell in love with as a high school student in Chino, which is 50 miles east of UCLA. But as a first-generation college student whose parents emigrated from India in the 1990s, she didn’t always see herself reflected in the students and faculty in that department.

An introductory course piqued her interest in labor studies, and there she found not only a program that will inspire her future, but a community of UCLA students whose experiences and perspectives were more like hers.

“I admit, it was kind of a culture shock at first,” she said. “I didn’t look like the traditional UCLA economics student. Then I found labor studies and found out I wasn’t alone at UCLA and I wasn’t alone in that feeling, that sense of ‘impostor syndrome’ that happens to so many first-gen or immigrant students.”

While economics coursework remained fascinating to Patel, she’s grateful for that first labor studies class that led her to double major.

“Economics is such a great degree because I felt like I could do anything with it: consulting, marketing, investment banking,” she said. “I come from a working class background — both of my parents work at a liquor store — so learning the history of the community was really personal to me. In labor studies, learning about working-class movements, you get to see the economy from workers’ perspective.”

Students in the program have been keeping in touch throughout quarantine, sharing resources for grant funding, coronavirus information, support for undocumented people, help with housing contracts and other advocacy efforts.

Patel is realistic about an uncertain job market. She’s hoping to get internships or take more online courses.

“I’m interested in public policy research and economic justice, nonprofit work or think tank work,” she said.

UCLA was Patel’s dream school from a young age, so being off-campus for her final quarter has been difficult.

“Ever since seventh grade when I visited on a class trip I just fell in love with UCLA,” Patel said. “I love the location, the people and I really didn’t think I would make it here, so when I got in, it was obvious that I would come to UCLA.”

Working-class students bring a valuable perspective

It’s a fascinating time to be an instructor, said Toby Higbie, who serves as chair of the labor studies major.

“It’s a different kind of curriculum and a different kind of student experience,” said Higbie, who is also a history professor. “It’s populated by an amazing group of students who are mainly first-gen from across the L.A. region, coming from working class families. Often they have experience as workers in the labor market already so they bring a different level of engagement on topics like farm workers, industrial regulations, labor law and labor history. They bring their personal experience to the classroom, which changes the conversation.”

The goal of the major is not just to impart knowledge, but to endow its students with the tools to become active in society in whatever way they want to whether that’s working for a union or as a lawyer, community leader or entrepreneur, Higbie said.

The community-building ethos of labor studies is a sentiment echoed by other graduating students.

Michelle Cervantes has spent much of her time during the pandemic volunteering to help with the hotel workers union by calling policymakers, working on a food drive and packaging food supplies for those out of work. She’s hoping her experiences with this group inspire UCLA to create paid fellowship programs that allow students to do this kind of work as part of their education.

Growing up in downtown L.A., a middle child of seven siblings, with a single mom who emigrated from Mexico, Cervantes said her childhood memories center around watching her mom work many hours at multiple jobs and multiple side hustles.

“But, still, we never had enough money,” Cervantes said. “I didn’t understand and it really stuck with me. My mom came to this country when she was 12 and her dream has been to see her kids go on to higher education.”

Cervantes is graduating with a double major in history and labor studies. After a gap year, she plans to go to law school, and post-graduation hopes to work at a litigation law firm to gain experience. She also plans to devote her free time to volunteering with nonprofits that focus on immigration to round out her knowledge of legislation and how it can benefit or detract from social justice movements.

Early in her time at UCLA, Cervantes felt first-hand some of the struggles of low-income workers, witnessing wage theft and experiencing personal intimidation at a now-closed Westwood restaurant where she worked during her sophomore year. In part, this is what drew her to the labor studies major.

“It made me want to be part of history, it made me want to organize,” she said. “One day I would love to work in an immigration law firm and also do something with civil lawsuits, protecting people from wage violations. Eventually I’d like to be an elected official, a D.A. or appointed official in a position of power to make changes in immigration legislation, in labor law.”

Cervantes also served as campus engagement director for the immigrant youth task force at UCLA. In some of her last work for the major, she completed a case study on immigrant workers as essential workers during the pandemic.

Labor studies students connect real-world research with their community

Students in labor studies participate in a summer intensive research class run by Saba Waheed, research director at the UCLA Labor Center and Janna Shadduck-Hérnandez, professor of labor studies one of the center’s project directors. For the last several years they have been working with labor studies students collecting and analyzing data that tells stories of student workers throughout the higher education system.

Seniors from the 2020 class said that real-world data gathering experience was invaluable.

“I fell in love with their way of teaching, their way of conducting research, their leadership as women,” said Mayte Ipatzi, who is graduating with a double major in sociology and labor studies.

Ipatzi is looking forward to the fact that data from this ongoing summer research project will be published soon, potentially by the end of June. It will also include information on how COVID-19 has affected working students.

“We’ve been analyzing identities and challenges for students who are enrolled full-time in L.A. County, and navigating also having to work,” Ipatzi said. “We’re looking at how this affects their mental health, and where do their paychecks go. I think the labor studies major does a really good job at inspiring us to really critique our economic systems.”

The lives of working students have changed dramatically over the last several decades as the cost of a college education wildly outpaces real wages.

Forty years ago, students who worked likely used some or all of that money for fun or leisure, but now paychecks are more likely going to tuition, housing, food, or even supporting their families, Ipatzi said.

Ipatzi has been serving as an academic peer counselor for UCLA, working 20 hours a week in spring quarter, along with her full course load and her internship with the Foundation for California Community Colleges

After commencement she has one last summer course to complete, then she plans to take a year off, study for the GRE to get into graduate school, and figure out the best trajectory for her goal to work as a counselor or social worker.

UCLA actually wasn’t her first choice, but Ipatzi got in to all of the schools she applied to, including UC Santa Cruz and UC Berkeley. A first-generation student born in Mexico City, but raised in Oxnard, California, Ipatzi accepted the UCLA offer sight unseen, thanks to a generous financial aid package.

“I really took a leap of faith, orientation was my first day on campus,” she said. “It was probably was one of the best decisions I have ever made and the best decision I could have made.”

Ipatzi has a brother in community college, who she is helping navigate the higher education process. She and her family are understandably disappointed at the fact that there will be no commencement ceremony this spring to celebrate her accomplishments in person.

“It’s that moment you play over and over in your mind like a movie, and it’s hard to know it’s not happening this year,” she said, “But if there is a ceremony later, of course I will come back and be the star of that movie.”

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.