A Q&A with the alumnus and longtime UCLA supporter on the power of the past to shape what’s next

“We are not gleaning enough of the past to have good fruit for the future,” Meyer Luskin said. “We must convince universities, and departments of history in universities, to point out … lessons for current society.”

By David N. Meyers

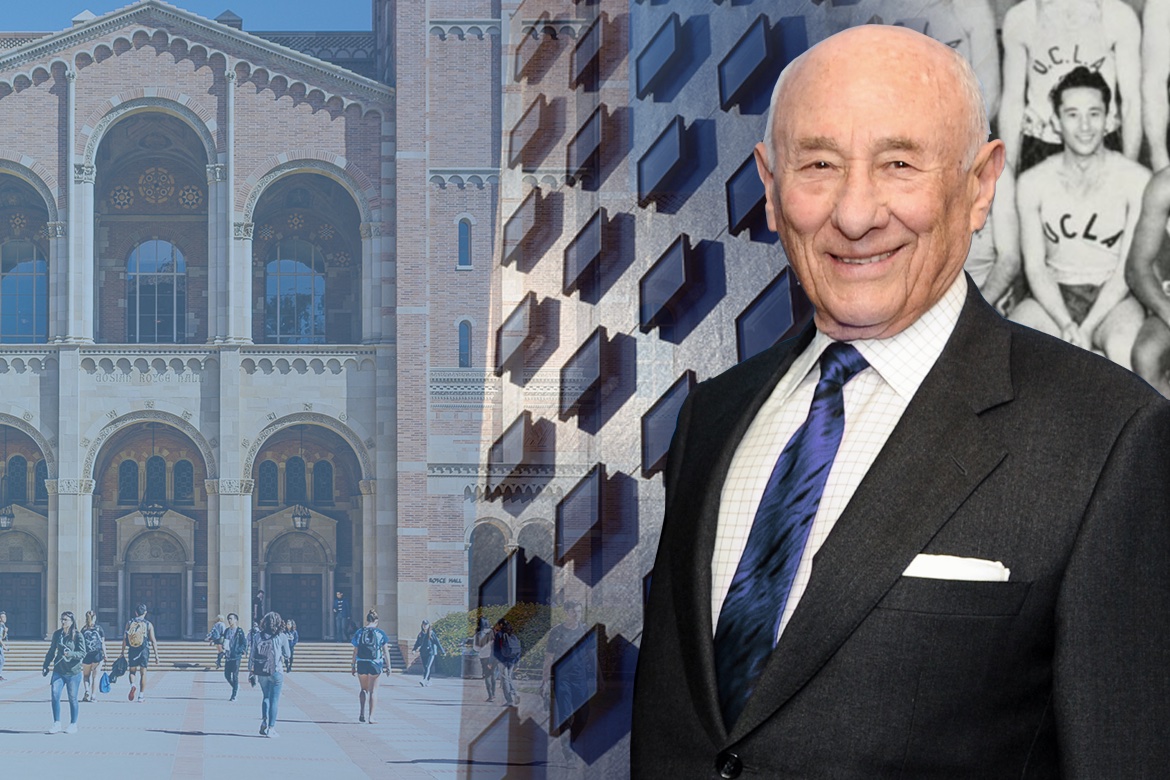

The impact of Meyer and Renee Luskin’s leadership and giving at UCLA cannot be overstated, with their generosity touching nearly every area of campus. As the alumni couple makes a landmark $25 million pledge to support the UCLA Department of History, Meyer took the time to share his thoughts about his first academic love — history — and why he believes it may have the ability to save us all, if we are wise enough to mind its lessons.

What was your journey to UCLA like?

I was born on the Lower East Side of New York and spent my first 14 years there. In the old days with the crowded tenements, I was really living in a ghetto with hardly any outlook on what the world was like. Then we moved to Boyle Heights, which was a little more expansive, but not a hell of a lot more. We were very poor; my life was surrounded and circumvented by being in an enclosed area. And then I’m off to UCLA and the world expands — suddenly, I see different people, different opportunities.

I had to travel an hour-and-a-half to get to UCLA because I had no car. It was a combination of a trolley on Brooklyn Avenue and then a streetcar, then a bus and then a walk of about half a mile. It wasn’t easy. I spent a year at UCLA from 1942 to 1943, went into World War II in the army and came back to UCLA in 1946. I finished my remaining three years and graduated in 1949. Then I got an M.B.A. at Stanford. One of the great things UCLA did for me was to open my world and mind to something more — and then give me the tools to go further.

How did your family influence your journey to UCLA and beyond?

My mother and father had no formal education, but they were intelligent people who, when they came over to this country, quickly learned to read and write English. My father was a working-class man, a plumber, but he insisted I get a good education and prepare myself for more. And so I did a great deal of reading as a youngster. What encouraged the reading was that I was a very sick child with all sorts of illnesses, so I was home a lot more than most children. It turned out I really enjoyed reading books of history, books of the people who affected history. It was primarily European history, Western history, but I did read some history of Asia and of other parts of the world. When I went to UCLA, I majored in history — that was my love. At UCLA, I delighted in being exposed to history on a higher level than I got in high school. When the professor would assign a chapter over a weekend, I’d spend all day Saturday and Sunday reading two or three books. I just couldn’t get enough. I had a class in European history as a freshman where I did so well that the professor asked me whether I wanted to read and grade exams for him. And my second semester, I did.

Meyer Luskin in a 1949 yearbook photo as a member of the UCLA boxing team. As a student, his first love was history.

Did you ever consider becoming a historian?

My world was so narrow that the concept of being a professor or historian was one that I didn’t quite grasp. For me, this kid from Boyle Heights, the distance between me and professors felt too vast, and I never thought I could do anything with my love for history. After I was discharged from the army in 1946, I wondered how I would make a living. I thought, well, I’ll change my major to economics. But I did take a couple of philosophy courses at UCLA which were of great value to me, because one of them was a course in inductive logic. Professor Hans Reichenbach taught me the value of understanding probability in everyday decisions, and it helped me a lot later in life.

In 2014, you gave an address at the UCLA history department commencement ceremony that made the point that history helped you avoid some big missteps. How so?

I was in the business world, with a company that had most of its assets tied up in oil rigs in Libya. This was before [Moammar] Gadhafi, before dictatorship; there was a king, Idris. All the major oil companies employed contractors to drill their wells; we owned 10 different rigs, which led to a lot of debt. And when I was in Libya, I became acquainted with a very intelligent, cultured Libyan who was one of our employees, and I had him explain to me the history, politics and background of the nation. I then realized that the king would probably be deposed, there would be a dictatorship that hated the West, and there was a good chance that this type of dictator would nationalize the oil industry.

So I made a point to sell our business in Libya. My colleagues thought I was crazy because it was very profitable. But several years after we sold our equipment in Libya, sure enough, along comes Moammar Gadhafi, who drives out every company. All of the contractors went broke, and some even had to ransom some of the men to get them out of the country. And so knowledge of history saved our butts. Truly understanding the industry, work and society you’re in helps you make much better decisions for the future.

What do you hope history can do for society, both now and in the future?

Who can better understand the past and derive knowledge that’s worthwhile for the present and future than historians? The historian has the ability to look back and research and truly understand — something too many of us are not doing enough of because we’re taken up with the daily problems of existence. Historians give us a sense of perspective — what went wrong, what went right — and educate our citizens and political and economic leaders. Their learning can lead us to a better path so we don’t repeat mistakes.

I’ll give you a good example of learning from history, in my opinion. After World War I, the nations that won — France, the United States, England — really penalized Germany and put onerous conditions on its existence. And as a result, we had a Germany that hated the rest of the world and gave birth to a horrible dictator. And we had World War II. After World War II, we realized there’s no point in once again trying to destroy Germany; by learning from the past, we came up with the Marshall Plan. France and Germany now work together, and we haven’t had a war in the western part of Europe since — all because we learned from history.

Meyer and Renee Luskin receive the 2021 Edward A. Dickson Alumni of the Year Award from the UCLA Alumni Association. “What drives Meyer and Renee,” Chancellor Gene Block said, “is precisely what drives UCLA: a desire to solve society’s biggest challenges and to create opportunity for all through education and research.”

With today’s immediacy of social media and misinformation, I wonder if one effect may be that we lose a sense of that long-term unfolding of history. Do you think it is a critical moment for recapturing what is so significant and beneficial to society about history?

I think you have it exactly right. What has gone on in the last 20, 30, 40 years, people are getting so taken up with the immediate that there is a lack of perspective. Rather than being able to sit and discuss and talk, drawing on the perspective of the past, people think solutions have to be immediate too. A society without long-term vision will lose the lessons of the past. I blame that on a lack of reading and too much focus on day-to-day stuff on our phones. We, as a society, have gone backward rather than forward in embracing long-term thinking.

Renee Luskin’s 1953 UCLA yearbook graduation photo. She earned her bachelor’s degree in sociology and went on to pursue social work at USC.

Did that feeling — that this moment is so critical — inspire you and Renee to make such a transformational gift to the department of history right now?

Exactly, because I’m so concerned about our country and our world. I want everyone to appreciate the value of where we’ve been, what’s happened, where were the mistakes and how we can avoid repeating them. It’s going to be a dangerous outcome if people continue to get so caught up in daily and transitory events without a true vision of where we’ve been and where we’re going. We have come too close to accepting dictatorship, which sells an illusion that a strong man on a horse is going to solve all the problems. In fact, that strong man on the horse winds up putting you in jail and killing you if you don’t agree with him. It’s more important than ever to look at history and the long-term picture.

You seem to me to be a staunch proponent of the famous aphorism delivered by the Harvard philosopher George Santayana: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

I’m thinking of what Mark Twain said — and I probably will get it wrong — but he says something like, “History may not repeat itself, but it surely rhymes.” We are not gleaning enough of the past to have good fruit for the future. We must convince universities, and departments of history in universities, to point out the similarities to and lessons for current society.

We need more articles published in the newspapers and on television of studies of how something in the past relates to exactly what’s going on right now. It would make for a better world for us all. I hope that other universities would also have their history departments emphasize the need to use their studies to educate the public more. I hope the UCLA history department sets the standard and leads in helping society understand what they’ve learned.

One last question. You and Renee have made remarkable and ample investments in UCLA. What does the university mean to you?

I believe in order to have a true democracy, we have to have a truly great public university. If the public of a nation does not have a place where they can go for higher learning and to be lifted, then you cannot make any progress, and you go backward. I believe that we must support the public university more than ever, which we’re doing. The knowledge of the world essentially emanates from the university.

I also think great ideas for humanity do not come solely from “hard” science; they also come from the “soft” sciences. UCLA in the fullest sense — all of its disciplines — must be supported. And history shall always be important for the progress of people.

Myers, the Sady and Ludwig Kahn Chair in Jewish History, is director of the UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy and the UCLA Initiative to Study Hate.

This article, written by David N. Myers, originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.