Jared Diamond celebrates 58-year UCLA career, reflects on his landmark sighting of the long-lost golden-fronted bowerbird

Álvaro Castillo | Art by Trever Ducoteer

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, opulent hats adorned with exotic bird feathers became a major trend in American and European fashion. But the lucrative plume trade came at an enormous ecological cost, with many fearing that overhunting would drive numerous bird species to extinction.

The golden-fronted bowerbird was one such threatened species. Previously known from only four skins found in a Paris feather shop in 1895, this New Guinea bird, which boasts a brilliant crest atop its head, was presumed for nearly a century to be a relic — and a victim — of Victorian fashion sensibilities. These specimens were proof of the birds’ existence, but other than being brought to France by Dutch Indie East plume traders by way of New Guinean hunters, little else about its origin was certain.

John Gerrard Keulemans

That is until 1981, when Jared Diamond, a UCLA professor of geography and physiology, rediscovered this elusive bird while exploring the Foja Mountains in Papua, Indonesia, approximately 179 miles south of the equator and uninhabited by humans

Diamond — who joined UCLA’s faculty in 1966, earned a MacArthur Fellowship in 1985 and the National Medal of Science in 1999 — was invited by the Indonesian New Guinea government in 1979 to survey the island and propose plans for the creation of a national parks system.

With a $1,000 grant from the government, he chartered a helicopter to explore the peaks of the Foja Mountains so he could collect general data on its wildlife and plants. But, like many bird enthusiasts, Diamond had a hunch this might be the place to find the golden-fronted bowerbird.

“Every scientist who came here had a dream in the back of his mind about finding the bird – the mystery bird of New Guinea,” Diamond said in a 1981 New York Times interview. But, alas, luck wasn’t on his side on this 1979 expedition.

Without the proper tools and equipment, there was no way to land the helicopter safely on the high-altitude marsh the pilot had identified.

“Here I am in paradise,” Diamond said, “and I can’t land there. I was crushed.”

Unfazed by the initial setback, Diamond returned to the Foja Mountains two years later, this time with a copilot who rappelled down from the hovering helicopter into a marsh and, using a chainsaw and some pieces of plywood, created a makeshift landing pad with felled trees.

And on Jan. 31, 1981 — the second day of the expedition and not far from where his New Guinean-led team set up camp — the first bird Diamond saw as he entered the forest was the golden-fronted bowerbird, marking the first-ever documented sighting of live specimens.

And what a show he saw: an azygous male performing its elaborate courting ritual, which involved displaying a bright blue fruit in its bill so it could be seen against the background of its yellow crest.

Additionally, Diamond had the opportunity to observe the intricately constructed bower — the source of the bird’s name and the signature gesture of its mating ritual. This unique structure, created solely by males to woo females, stands 3 to 4 feet tall and is made from sticks, twigs and foliage and embellished with fruits and flowers.

Diamond remembers, with a smile, one of his former UCLA student’s reactions when he shared his observation that male bowerbirds with the dullest plumage tend to have the fanciest bowers, and vice versa.

“‘Aha! That’s just like men who own sports cars,’” Diamond recalls the student saying. “I myself have no opinion on this matter.”

Diamond’s pioneering expeditions to the Foja Mountains not only led to the rediscovery of the golden-fronted bowerbird but also established a blueprint for other scientists seeking to explore and document the world’s second-largest island after Greenland.

In 2005, Bruce Beehler, an American ornithologist and research associate at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, led an international team of scientists and returned to the Fojas, successfully photographing the golden-fronted bowerbird for the first time. (Diamond also photographed the bird in 1981, but during a perilous boat journey between islands, the boat overturned and the film was lost.

Beehler is credited with finding the home and confirming the existence of Berlepsch’s six-wired bird of paradise, the other long-lost New Guinea bird who previously only existed in most of humanity’s imagination as decorations on Victorian hats.

For nearly a century, scientists knew little about this mythical bird, but as it turns out, Diamond’s inkling about this equatorial mountain range was spot on.

“The golden-fronted bowerbird and Berlepsch’s six-wired bird of paradise were the only two lost-long New Guinea birds — and they both turned up in the Foja Mountains,” Diamond said.

As Diamond looks back on his historic rediscovery, he also marks another remarkable accomplishment — he retired from UCLA in 2024 after a remarkable 58-year career here that began in 1966.

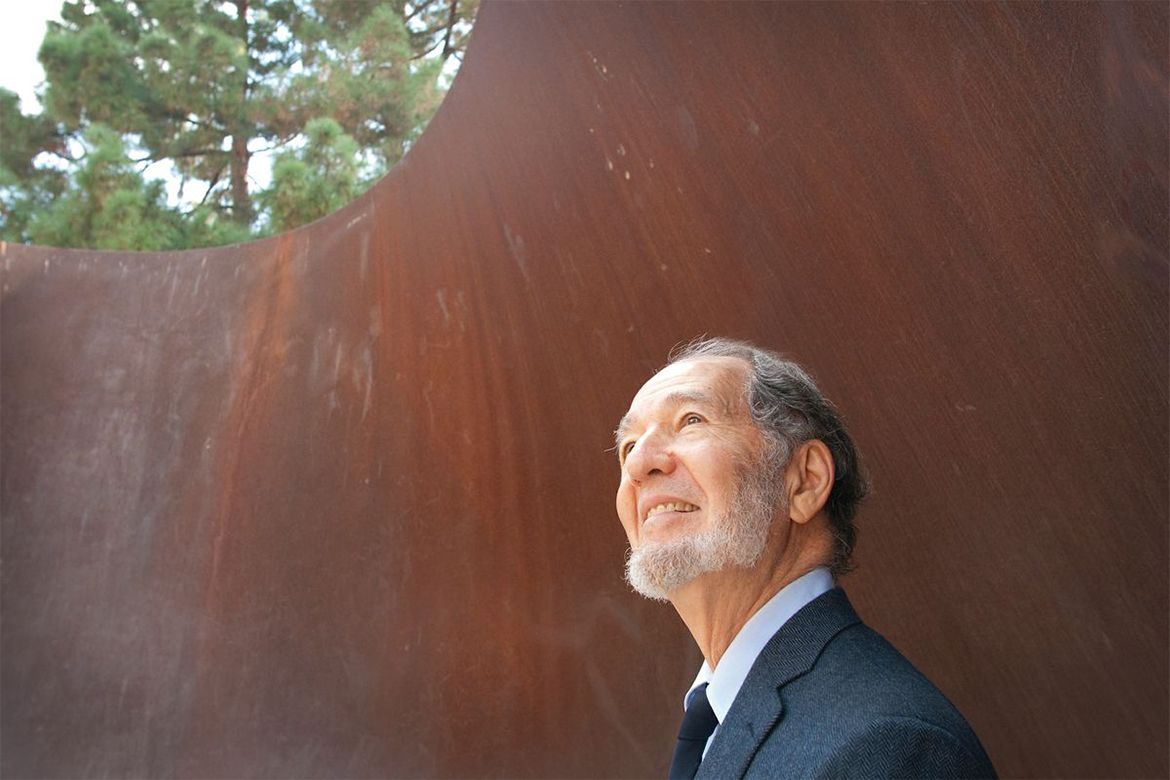

Diamond’s life and academic curiosity would be forever linked to New Guinea after his first trip to the island in 1964. / Pamela Springsteen

“There’s a chance that I’ve been the longest-serving faculty member at UCLA,” Diamond said. “I’ve had a very good time at UCLA and am grateful to our institution and the UCLA students I’ve had the pleasure of working with throughout the decades.”

As a geographer, Diamond’s insight and intellect are best reflected in his acclaimed bestsellers “Collapse,” “The World Until Yesterday” and “Guns, Germs and Steel,” the latter earning him a Pulitzer Prize for groundbreaking work exploring the environmental and geographical factors that have shaped human history.

Diamond’s robust body of research — which combines diverse and seemingly unconnected topics such as the domestication of animals, the origins of smoking and drug use, the reason for menopause, the development of the Indo-European family of languages, the displacement of Native Americans, the biology of New Guinea birds, digestive physiology and conservation biology — earned him numerous distinctions, including election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.

Overall, Diamond’s nearly six decades at UCLA showcase a simple truth: He is that rare scientist who can speak to the public – and be understood.

This story was originally published in the UCLA Newsroom on January 31, 2025