Participants in social safety net programs had higher rates of employment, were less reliant on public assistance

Citlalli Chávez-Nava

As federal social safety net programs face elimination or budgetary reductions under the new administration, a UCLA report has found some of the boldest War on Poverty programs launched in the 1960s and 1970s reduced poverty and improved upward mobility and well-being.

Launched in 1964 by President Lyndon Johnson’s administration, the War on Poverty represented one of the largest and most comprehensive attempts to improve well-being in United States history. The administration invested billions of dollars in education, health, employment and community development initiatives — including Head Start, an expanded food stamp program, family planning programs and community health centers. The campaign targeted the roots of poverty, seeking to provide a “hand up, not a handout.”

The study, recently published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, looks at how access to these programs for children in the 1960s and 1970s shaped the outcomes and living circumstances of tens of millions of adults today, using newly available large-scale data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Social Security Administration. The decades-long research was led by Martha Bailey, professor of economics and director of the California Center for Population Research at UCLA.

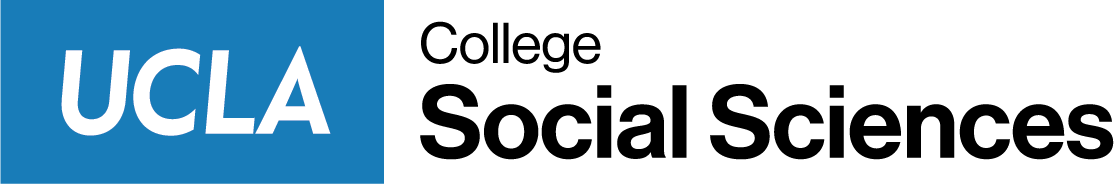

Head Start, which aimed to reduce poverty and still serves 1 million children today, offers early education to preschool and kindergarten-aged children, nutritious meals and referrals to health and other social services. But for decades, evaluating the program’s success in helping children escape poverty was difficult since researchers faced data challenges in identifying valid comparison groups.

Using the newly available data, researchers measured Head Start’s success in terms of children’s later-life educational attainment, work in professional occupations, participation in the labor force and wage earnings. Researchers compared children who were born a few months too soon to enroll during Head Start’s initial rollout with children who did enroll. Head Start children were significantly more likely to finish high school and enroll in and finish college than peers who entered first grade without access to the program (Figure 1). The results also show that cohorts with access to Head Start experienced lower rates of adult poverty, had higher rates of employment and were less likely to have received public assistance.

“It’s important to consider the long-run consequences of public programs,” Bailey said. “Investing in children is like planting a seed. Many of the programs starting in the 1960s are still having measurable effects today.”

Based on analyses of hundreds of on-the-ground programs across the U.S., the report also found:

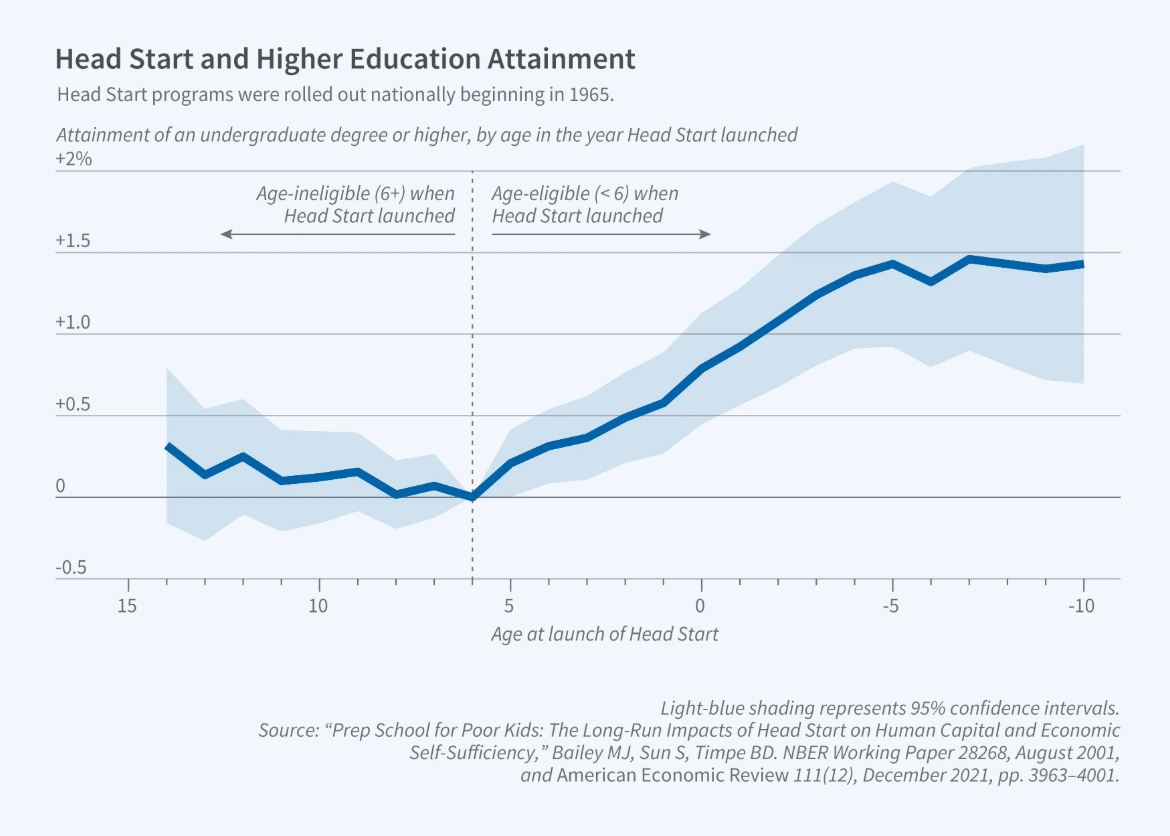

- Greater access in a child’s early years to the Food Stamps Program, known today as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, was associated with significant increases in educational attainment, economic self-sufficiency, and neighborhood quality and reductions in physical disability. The timing and duration of early food stamps access also impacted outcomes. (Figure 2)

- Federal family planning programs affected children’s resources and long-term outcomes. The programs allowed parents to delay childbearing and to find more stable partners and better-paying jobs, reduced their dependence on public assistance and decreased their likelihood of being in poverty.

- Community health centers located in disadvantaged neighborhoods resulted in significant declines in age-adjusted mortality, particularly from cardiovascular disease among adults over 50. These reductions in mortality were highly persistent, decreasing the gap in mortality between the poor and non-poor by 20% to 40% for 25 years. Today, these programs continue as federally qualified health centers.

“The data show that U.S. poverty rates, health, human capital and employment outcomes would have been worse today without the substantial investments made under the War on Poverty,” Bailey said. “In many cases, the benefits of the programs well exceeded their costs.”

This story was originally published in UCLA’s Newsroom, here.