Susan Slyomovics receives American Anthropological Association book award

Lynch plans to return to Brazil to further collaborate with a network of researchers at Brazil’s National Primate Center during spring 2026.

Victoria Gutierrez’s senior research examines how Salton Sea residents organize to overcome poverty, environmental challenges

Sean Brenner | May 7, 2025

The research project Victoria Gutierrez is completing as a UCLA senior was inspired by a set of photographs she saw years before she set foot on campus.

As a 14-year-old, Gutierrez came across pictures of Salvation Mountain, the massive, colorfully painted folk art installation in the midst of a barren desert landscape in the Salton Sea region of southern California.

“I remember thinking, ‘What is this place? I have to go there,’” she said. The thought stayed with her over the next few years, and she pondered the small communities of people living there.

“It’s very beautiful, but it’s very desolate, plants don’t really grow and it’s known for having toxic dust that comes from the Salton Sea,” Gutierrez said. “I just wondered, how do people live there, how do they cook, how do they do this? Those questions just lived in my brain for a long time.”

Shortly after Gutierrez arrived at UCLA — the Rhode Island native transferred in 2023 from Saddleback College — the opportunity to explore those questions arose. Determined to pursue her own research project, she set up a meeting at the Undergraduate Research Center. It was there that a UCLA graduate student named Jewell Humphrey suggested that Gutierrez think about what questions she had always wanted to find answers to.

The Salton Sea came immediately to mind.

After she discussed possible research approaches with UCLA anthropology professors Jason De León and Jason Throop, Gutierrez had a concept for a sophisticated anthropological study. The project, which is supported by the UCLA/Keck Humanistic Inquiry Undergraduate Research Program, focuses on how residents of Bombay Beach and Slab City cope with the ecological damage, extreme poverty and limited government support they face — and how they organize in an attempt to overcome those challenges.

“Victoria’s project seeks to understand the experiences of those living on the margins in rural California and how people attempt to build community in places where infrastructure, poverty and climate change work to disrupt social networks,” said De León, who also has a faculty appointment in Chicana and Chicano studies and is a member of the Cotsen Institute of Archeology.

“As we move into a new era of climate change whereby the haves and have-nots differentially experience things like droughts, rising temperatures and other catastrophic environmental events, projects such as Victoria’s will become increasingly important. I applaud her for tackling such an important social issue.”

Over the past year, Gutierrez has conducted dozens of interviews with residents and spent weeks living among them, even volunteering at a cooling center — a climate-controlled trailer where locals can escape the oppressive heat.

“I’d do 12-hour shifts, just making sure the air conditioning was on,” she said. “People would come in, and I would get to talk to them for really long periods of time.”

Initially, Gutierrez planned to focus on the role of climate change in the region, but she changed gears when she realized residents were more focused on their efforts to improve their communities. One woman she interviewed was applying for grants to build a park in Bombay Beach.

“I was really inspired by how these people kept wanting to do better for themselves, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles,” said Gutierrez, a political science major and anthropology minor.

Her study also highlights the stark realities of poverty. Many residents told her they had ended up in the area mostly because they had nowhere else to go. She recounted the story of one woman, Belinda, who had been arrested as a teenager and never had access to formal education.

“She is functionally illiterate, has no degree and suffers from severe health conditions,” Gutierrez said. “If she lived in L.A., she’d probably be in far worse conditions. But in Bombay Beach, she’s welcomed and seen as a respectable member of society.”

Gutierrez’s study is timely: In January, a judge cleared the way for a long-planned project that will mine large amounts of lithium from the ground beneath the Salton Sea. Lithium is an essential component of electric car batteries, mobile phones and numerous other products, and the region is said to have an enormous supply, so the potential economic benefits are obvious. But the possible ecological consequences, in particular, have worried locals and environmental activists.

“It’s really curious that the first meaningful efforts to clean up the Salton Sea are happening just two years after it was declared the largest domestic deposit of lithium,” Gutierrez said.

And although the communities of the Salton Sea face an unusual set of challenges, Gutierrez said her research has made clear that the region holds lessons for everyone, no matter where they live.

“One of my biggest takeaways is that we’re all a lot closer to being in a situation like Bombay Beach than we think,” she said. “With climate change, wildfires and economic instability, these issues aren’t as far removed as they seem.”

Gutierrez is still deciding what her next steps after graduation will be, but one way or another, she’s determined to continue studying the region. “I love the Salton Sea,” she said. “I feel very lucky that I know what I care about.”

This story was originally published via UCLA Humanities.

UCLA Anthropology

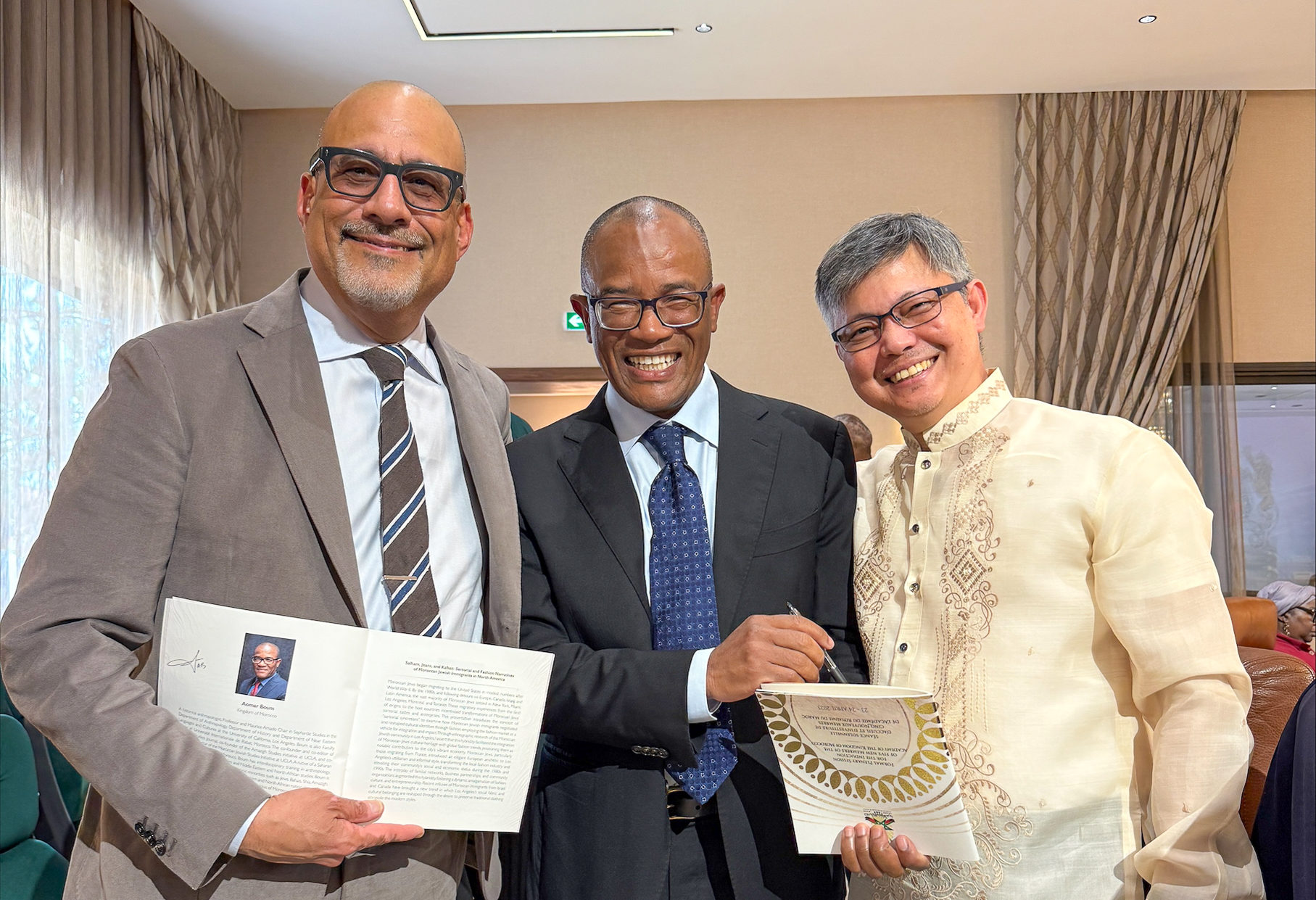

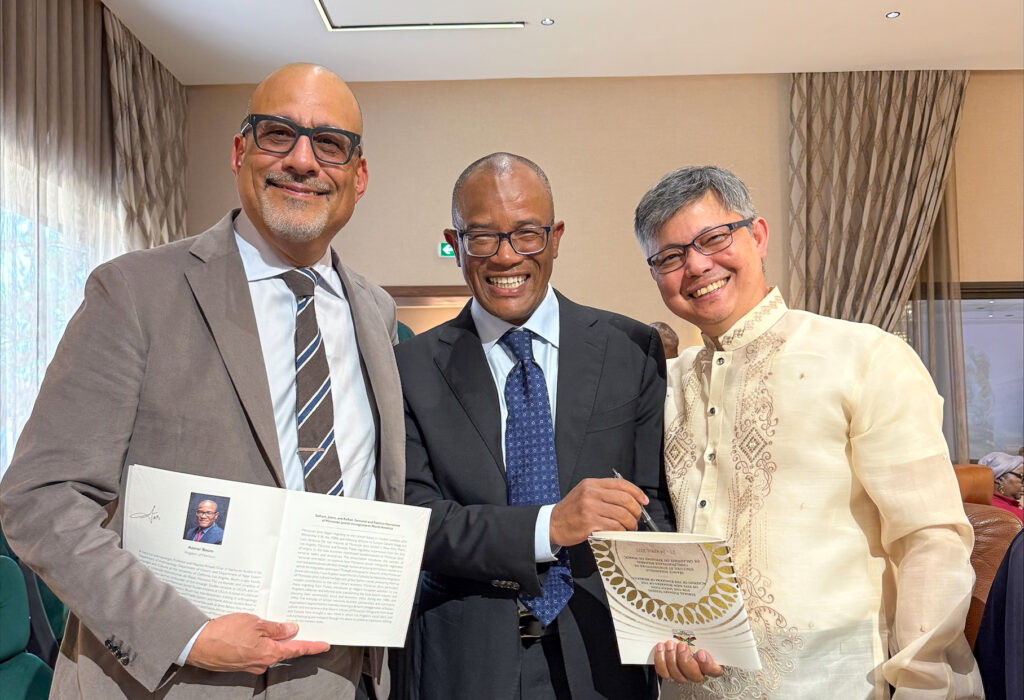

Abel Valenzuela, Aomar Boum and Stephen Acabado (left to right) at National Academy ceremony of the Kingdom of Morocco./UCLA Anthropology

Aomar Boum, professor of anthropology and of Near Eastern languages and cultures at UCLA, was inducted into the National Academy of the Kingdom of Morocco at a ceremony held April 24 in Rabat, Morocco.

It was a moment that brought together so many parts of his life, connecting his early years in Morocco to his years of scholarship and community building abroad. True to form, Boum began his remarks by thanking the mentors, colleagues, friends and family members who had guided and supported him throughout his scholarly and personal growth.

“That introduction was overwhelming in the best way. I truly can’t thank my mentors and family enough for their support,” Boum said.

It was also a proud and emotional moment for Boum’s colleagues who have witnessed his dedication and impact over the years.

“Aomar’s work has always shown us how community histories are deeply tied to landscapes. It’s only fitting that our new UCLA-UIR (Université Internationale de Rabat) Highland Ecology Project in Morocco builds on his legacy — centering local knowledge, memory, and the environment,” said Stephen Acabado, fellow professor of anthropology and chair of the UCLA’s Archaeology Interdepartmental Program, who attended the ceremony.

Born in Foum Zguid, in Tata province, Boum’s early experiences in a Saharan Amazigh community shaped the way he approaches history, identity and belonging. Today, he holds appointments in the departments of anthropology, history and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures at UCLA. His research has centered on the complexities of religious and ethnic minorities in North Africa, and his work has challenged and broadened the narratives about Jewish-Muslim relations across the Middle East and North Africa.

At the induction ceremony, Boum delivered a lecture that captured the spirit of his scholarship: Salham, Jeans, and Kaftan: Sartorial and Fashion Narratives of Moroccan Jewish Immigrants in North America. In this talk, he explored how the Moroccan Jewish community in Los Angeles integrated into the larger LA community through global fashion trends, positioning themselves not on the margins but as notable contributors to the city’s economy. Boum introduced the concept of “sartorial syncretism” to describe how Moroccan Jewish immigrants negotiated and reshaped cultural identities through fashion, using the marketplace and style as vehicles for integration, entrepreneurship and cultural impact.

“His lecture was an eye-opening and textured portrait of migration, identity and economic creativity — areas where Aomar’s work continues to open new conversations,” said Acabado.

The ceremony was made even more meaningful by the presence of UCLA Division of Social Sciences Dean Abel Valenzuela, who traveled to Morocco to honor Boum’s achievements. Dean Valenzuela’s attendance reflected the respect Boum commands not only at UCLA but also globally.

“It was a complete honor to be in attendance to celebrate Professor Boum,” said Dean Valenzuela. “His research represents what UCLA does best — engaged, interdisciplinary scholarship that crosses borders and connects communities.”

Boum’s election to the National Academy affirms the significance of his work and the reach of his scholarship. It is also a proud moment for anthropology, especially among his colleagues in the Department of Anthropology at UCLA, who have long recognized the depth and impact of his contributions.

“Boum’s work reminds us how histories of migration, belonging and creativity can reshape how we understand our shared worlds,” added Acabado.

Related Story: UCLA College | Aomar Boum believes in the power of stories to unite

Adapted from UCLA Newsroom

Right to left: Marjorie Harness Goodwin (anthropology) and Jeffrey Lewis (political science).

Distinguished research professor of anthropology Marjorie Harness Goodwin and Professor of Political Science Jeffrey Lewis have been selected to the American Academy of Arts, one of the nation’s most prestigious honorary societies. They are among four UCLA faculty and nearly 250 artists, scholars, scientists and leaders in the public, nonprofit and private sectors chosen for membership this year.

The academy serves as an independent research center convening leaders from across disciplines, professions and perspectives to address significant challenges, with the aim of producing independent and pragmatic studies that inform national and global policy and benefit the public.

They will be inducted in October at the academy’s headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Marjorie Harness Goodwin

Distinguished research professor of anthropology

Goodwin, a linguistic anthropologist, focuses on how language, touch and other embodied practices shape human interactions. Her work has examined how members of children’s peer groups, families and workplace groups use everyday language and communication to construct social order, express intimacy and navigate ideas about moral behavior. Through her research and influential books, including “The Hidden Life of Girls,” “He-Said-She-Said” and “Embodied Family Choreography,” Goodwin has helped advance our understanding of human social dynamics and the ways people use their language, their bodies and their emotions to manage relationships and create meaning.

Jeffrey Lewis

Professor of political science

Lewis, a political scientist, investigates foundational questions of democratic representation and develops innovative methods for analyzing political behavior. His research explores how preferences can be deduced from behavior. He is also a leading figure in political methodology, contributing tools that have reshaped how scholars study legislatures and electoral politics. As the curator of Voteview.com — a platform that provides free data and tools for analyzing roll call voting in the U.S. Congress — he helps advance public and scholarly understanding of ideological polarization and legislative behavior. Lewis has served as president of the Society for Political Methodology and as an editor of the American Political Science Review, helping to shape the direction of research in the discipline. Through his empirical rigor and public scholarship, Lewis has played a pivotal role in elevating both the accessibility and sophistication of political science research.

Read American Academy of Arts & Sciences announcement here.

Learn more via UCLA Newsroom coverage here.