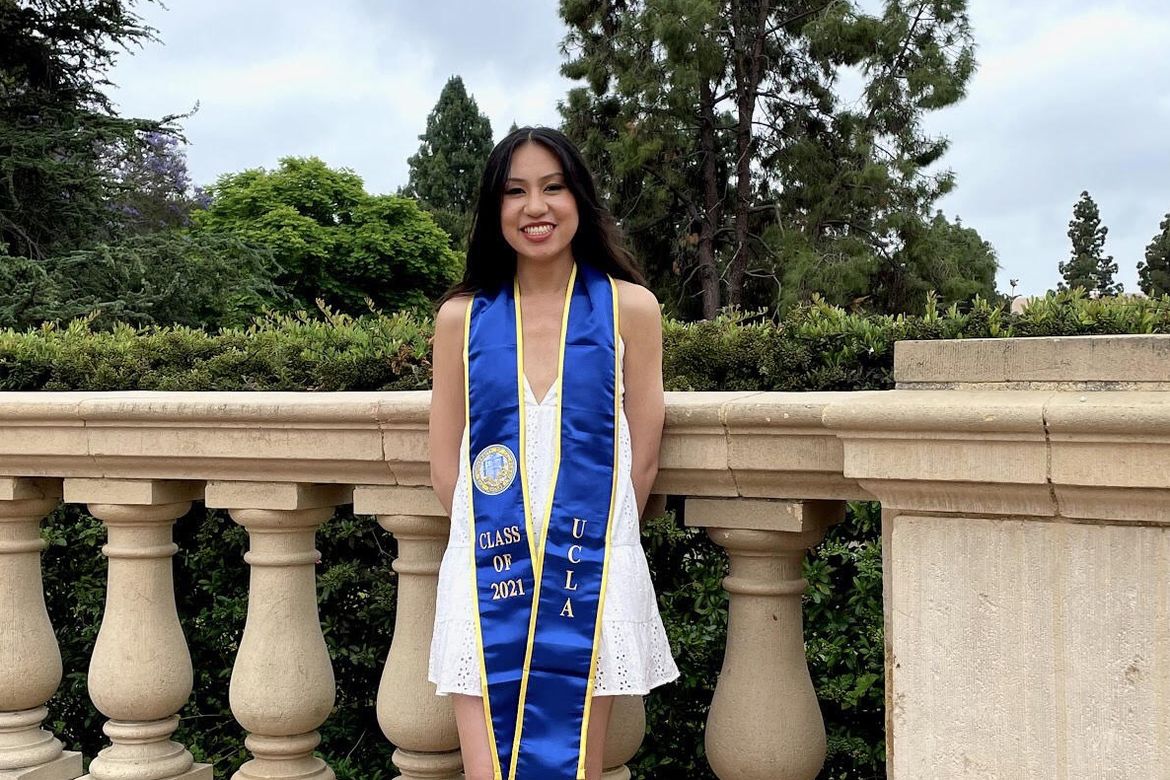

UCLA professor Renee Tajima-Peña, series producer of “Asian Americans.” (Photo Credit: Claudio Rocha)

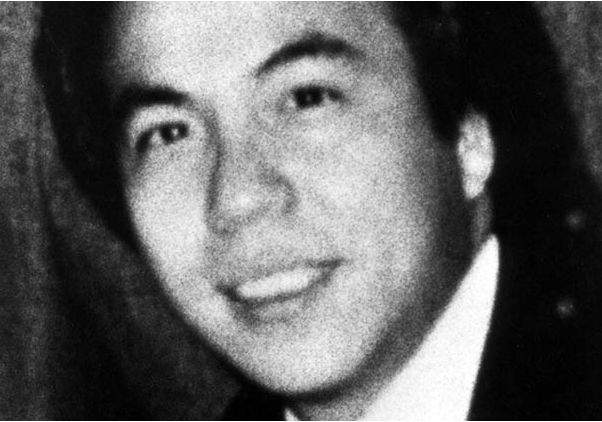

n 1982, a young Chinese American man named Vincent Chin was beaten to death as he was out celebrating his bachelor party in Highland Park, Michigan, near Detroit. America was fraught and tense, in the middle of a recession that had hit automakers particularly hard, given the rise of economically desirable Japanese cars. Racial animosity toward Asian Americans was running high.

Chin’s death and the relatively lenient sentence laid upon his two white attackers — one a recently laid-off autoworker in the city — were a shock to Asian American communities and sparked a wave of civil rights activism.

“There were lot of people at the time who thought, ‘I’m OK, I’ve made it, everything is OK,’ and then they were really awakened by the case,” said Renee Tajima-Peña, a UCLA professor and director of the Center for EthnoCommunications in the UCLA Asian American Studies Center.

Chin’s story is just one of many told in “Asian Americans” a five-part series that airs on PBS over two nights, May 11 and 12. It’s a story that Tajima-Peña knows well. She co-directed an Academy Award–nominated documentary about Chin’s murder.

Vincent Chin, who was murdered in Michigan in 1982. (Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Tajima-Peña also served as series producer for “Asian Americans.” And, while she has been working on the project for nearly two years, the timing of its release feels particularly potent, and unfortunately familiar, given the hate speech and even physical attacks that have been levied at people who might look Chinese in the wake of the crippling economic and health crises brought about by the spread of COVID-19.

“We’ve seen all of this before, but the question is, what’s our takeaway from this history?” she said. “To me, the takeaway is for people to find a way to support each other. The series is really future-oriented, even though it’s about history. The U.S has become more diverse yet more divided. When that happens, you’ve got to figure things out because we can’t move forward divided in this country.”

It’s also a personal history for Tajima-Peña, whose ancestors came to the United States from Japan in the early 1900s, a time when national law prevented the immigration of certain Asian groups. “My family arrived during the exclusion, they were on skid row during the Depression, they were incarcerated during World War II,” she said.

Her family’s story dovetails with the stories of subsequent generations of Asian Americans who came to the U.S. as immigrants and as refugees from the Korean and Vietnam wars. “People found a way to thrive,” she said. “And Asian Americans have been a part of moving this democracy forward throughout its history.”

Showcasing this reality is one of the overarching goals of the series. The episodes include a wealth of interviews with artists, activists and scholars.

It also quickly became a very UCLA-centric project. Grace Lee, an alumna of UCLA’s School of Theater, Film and Television, directed two of the episodes. Several other alumni served as crew on multiple episodes. And David Yoo, a professor of Asian American studies and history and vice provost of the UCLA Institute of American Cultures, served as lead scholar on the project.

“As an epicenter of Asian American and Pacific Islander communities and arguably the most diverse city in the world, the greater Los Angeles area is a generative space,” Yoo said. “This is not new for AAPIs and other communities, and many legacies are reflected in the series, including the remarkable contributions of UCLA Asian American studies, in terms of our students, alumni, staff, faculty and programs like EthnoCommunications, which has produced so many talented filmmakers.”

Solidarity is a running theme within the series. The Asian American community is itself the most diverse of any racial group and has faced internal racial conflicts, Tajima-Peña pointed out. But, she said, civil rights leaders past and present recognize that the struggle must always include other marginalized groups within the prevailing racial tensions of America.

“Asian American history is a history of solidarity,” she said. “People may see us as the model minority, but Asian Americans have been fighting from the very beginning. The biggest labor strike in the 1860s was by Chinese railroad workers.”

Tajima-Peña was delighted to find footage of Hawaiian-born Patsy Mink, the first female U.S. congressperson of color, speaking to the Democratic National Convention in the 1960s. Mink urged delegates to stay firm on a civil rights platform.

“What we wanted to lead to in the series is really the question of today, when we are a larger population with a greater presence in society — to quote from Richard Pryor, does justice mean ’just us?’” Tajima-Peña said. “That’s what we need to focus on, because people really want to get to work.”

Yoo said he hopes viewers will be inspired by the stories of civil rights efforts from the 1960s and 1970s. “The activism, struggle and creativity of that era set into motion remarkable efforts for social justice that provide a foundation which we can draw upon to engage the concerns of today,” he said.

The series is organized around personal stories, ones that will hopefully engender empathy and connection.

“These stories we are telling are personal stories around tipping points in history, and at these points, Asian Americans have found a way to work amongst themselves or work across ethnicities,” Tajima-Peña said. “You don’t have to be Asian yourself to see yourself in these stories.”

Wong Kim Ark, whose U.S. Supreme Court case led to a change in citizenship laws. (Photo: Public domain)

When Tajima-Peña thinks of hope, she thinks of young Asian Americans, some of whom might be experiencing the effects of racism for the first time. She thinks of their potential. She thinks of the stories of other young Asian Americans that came before and brought hope with them.

The series is bookended by two of their stories.

Wong Kim Ark was the son of Chinese railroad workers. He was born in San Francisco, where his parents legally resided at the time of his birth. In 1880, after a trip to China, he was denied entry back into the country on the grounds that he was not a citizen. Just 21 years old, he chose to fight — and took his struggle all the way to the Supreme Court. The landmark 1898 ruling in his favor established birthright citizenship for children born in the United States to parents who were not citizens.

“Asian Americans” also tells the story of Tereza Lee, who migrated from South Korea with her parents. Known as the first “Dreamer,” in the late 1990s, she fought for herself and other undocumented children through the DREAM Act, which ultimately failed to pass Congress after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, changed political thinking around immigration.

“She kept on fighting and joined a movement of other undocumented young people,” Tajima-Peña said. “And my own parents are citizens because of Wong Kim Ark. The inspiration of those two ends of the Asian American story is what will take us into the future.”

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.