By Elizabeth Kivowitz

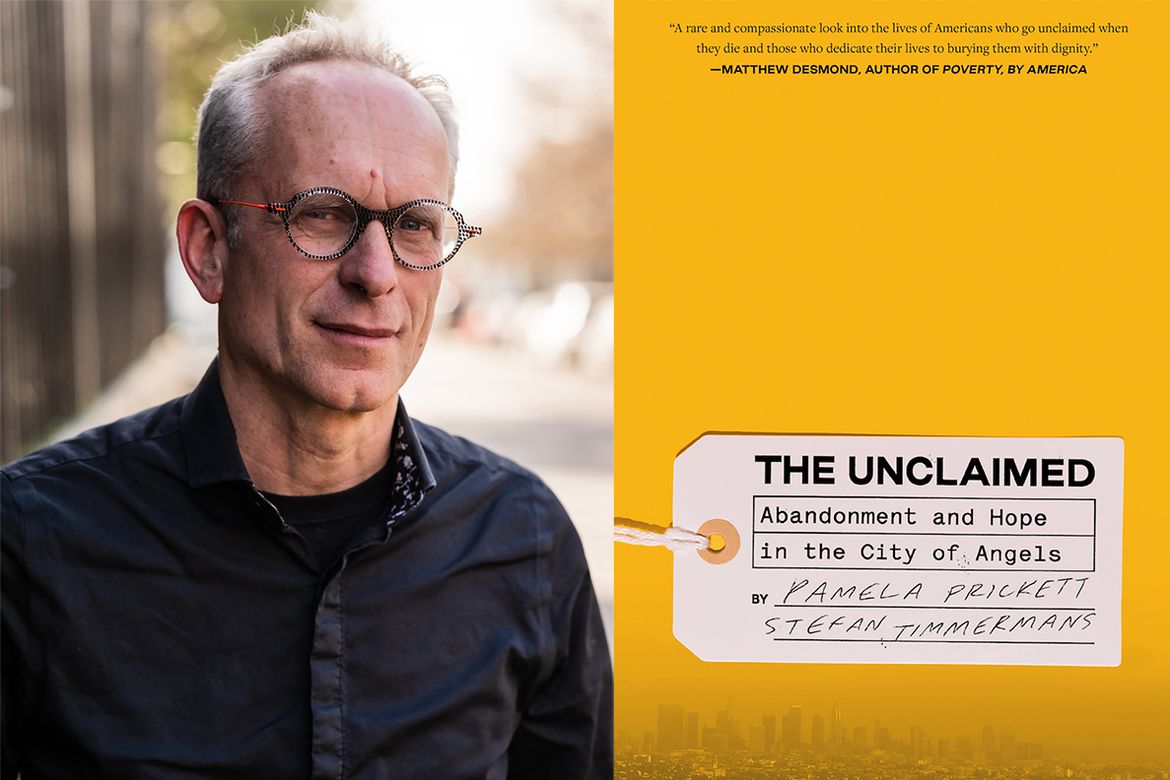

Based on their seven years of research, UCLA sociologist Stefan Timmermans and Pamela Prickett from the University of Amsterdam have published “The Unclaimed: Abandonment and Hope in the City of Angels.”

The book follows the lives, deaths and ultimately, the remains, of four Angelenos at risk of being “unclaimed,” meaning that upon their death, relatives or loved ones are unable or unwilling to bury them or to have their bodies cremated. Also included in the book are volunteers, community members and government workers dedicated to providing burials for unclaimed strangers, imparting a sense of dignity after death.

Timmermans, also the author of the award-winning book, “Postmortem: How Medical Examiners Explain Suspicious Deaths,” explores how contemporary society makes sense of sudden, unexpected or violent deaths and how the unfortunate end for the unclaimed should be addressed.

Why did you decide to write about the unclaimed?

No one grows up and says, “I hope that when I die, there is no one to mourn me.” My co-author Pamela Prickett and I were interested in what happens in a human life that makes someone go unclaimed in the end. What do we do with unclaimed bodies if relatives decline burial or cremation, and what motivates people to volunteer to bury unclaimed dead who are strangers to them?

Is being unclaimed a growing phenomenon?

The poor have always been more likely than the wealthy to be buried in unmarked graves and so-called potter’s fields. But today, Americans from all walks of life –– including people with jobs and homes and families who think they did everything right to prepare for old age — are ending up with a similar fate. An estimated 2% to 4% of the 2.8 million people who die every year in the United States go unclaimed — up to 148,000 Americans. This is roughly how many Americans die annually from diabetes. And that number is increasing. In Los Angeles County, the most populous county in the United States, the unclaimed used to make up 1.2% of adult deaths. Since the 1970s, that number has been rising and was up to 3% at the turn of the century. The increase means that hundreds more residents every year end up in a mass grave.

Why do we feel a sense of loss when we hear about growing numbers of unclaimed?

Going unclaimed goes against what makes us human. For as long as humans have existed, we have engaged in rituals to mourn and bury the dead. Even our ancestors in the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods buried their dead. It is precisely because burial is not a biological necessity, philosophers have argued, that its existence proves we are ethical beings, driven not just by nature but a cultural logic.

What does the prevalence of the unclaimed tell us about ourselves, our families and society at large?

The unclaimed are a sensitive barometer of kin support at the end of life. They reveal a hidden truth about the extent of family estrangement in America, as well as widespread social isolation and loneliness in contemporary society.

Shifts in the number of unclaimed remains across history tell us that something fundamental has changed in what Americans are willing to do for their relatives — and it’s far less than in generations past. Many of us can no longer take for granted that we will have someone to care for our bodies after we die. We will become more dependent on local governments to arrange our burials or cremations, putting us at the mercy of strangers and strained government budgets.

What is the book’s connection to Los Angeles?

The research took place in Los Angeles. We observed how county government officials in the office of the medical examiner, the public administrator and the department of decedent affairs retrieved unclaimed bodies and worked to notify relatives. We saw how employees in these offices, as well as strangers, come together to witness the burial of the ashes of the unclaimed, that are buried in a mass grave in Boyle Heights every year, if their cremains have gone unclaimed for three years.

Los Angeles may seem an unlikely haven in this haphazard landscape of loneliness and loss. It is after all, a city mocked around the world as superficial — the land of swimming pools, celebrities, ubiquitous blue skies and green juices. But L.A. has committed to bringing dignity to people who die vulnerable and alone. Indeed, L.A., and the Boyle Heights annual ceremony have shown people around the world that caring for the unclaimed dead can be deeply meaningful.

What policy changes or efficiencies could decrease the number of unclaimed? Do you have any recommendations?

Solving the problem of rising numbers of unclaimed bodies needs to start in life. We have been struck by how people who lived invisible and isolated lives received a flurry of government attention to locate their next of kin and dispose of their remains once they died. If only we could pour these resources back into life to intervene before people become disconnected and estranged. Social isolation is much less likely to lead to going unclaimed if people reside in communities that stabilize lives and strengthen human connections. U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy has called for a national strategy to prioritize social connections across local and national policies.

While it’s tempting to romanticize the idea of a return to the close-knit, multigenerational family, where siblings, spouses and children stand shoulder to shoulder in life and death, the lives of the unclaimed confirm that fewer and fewer people reside in such families. Instead, we need to recognize and foster the deeply meaningful connections of alternative family forms, such as cohabitation, companionship after divorce, deep friendship and involvement in religious groups. Often government officials stand in the way of people wanting to claim bodies because friends and other relatives don’t qualify as the legal next of kin. The next of kin should be selected on the quality of the relationship with the deceased, rather than on a legally sanctioned family tie.

We also need to strengthen the frayed social safety net. All too often, people who did everything possible to thrive in old age end up broke when they need intensive elderly care. There are no funds left for their funeral, and their relatives are faced with a large, unexpected expense.

Why do volunteers get involved in providing dignified burials for the unclaimed?

When strangers to the deceased stand in the gap left by relatives, they rally to mourn the abandoned. Ceremonies for the unclaimed have sprung up around the globe, motivated by the human conviction that every human deserves a proper funeral. In India, a woman made it her life’s mission to bury unclaimed bodies after her brother died a tragic death and her family was unable to conduct funeral rites. The homeless, poor and forgotten of Lafayette Parish in Louisiana are buried during an annual All Souls Day Mass, with public volunteers as pallbearers. In Erie County, New York, volunteers at a ceremony for the unclaimed each received a bag of cremains to spread in a straight line between imposing pines. High school seniors at the all-boys Roxbury Latin School participate as pallbearers in the burial of unclaimed Boston residents and bear witness to those who died alone. At the funeral of one lonely man, the seniors read as a group: “He died alone with no family to comfort him. Today we are his family, we are here as his sons.”

Is this a book about hope? If so, how?

Because the unclaimed end up abandoned in death as in life, burying them is an incubator for what sociologist Ruha Benjamin calls viral justice, small acts of justice based on care, democratic participation and solidarity, which inspire larger community movements. We have seen how attending funerals of the unclaimed spreads awareness about the high suicide rate among veterans, the desolation of recent migrants, and the power of radical kindness. Respect in death can be a rallying call for respect in life. Holding hands with strangers around the gravesite of the unclaimed as surrogate family members is an act of forgiveness and hope, seeding new viral justice opportunities. These funerals turn anger, sadness and sorrow into awareness, healing and connection. Even if it may seem there are other social problems more pressing and worthy of our limited time, the unclaimed remind us that unless every body counts, nobody counts.

What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

“The Unclaimed” is a wake-up call to take stock of what matters in life: social relationships. The book poses the haunting question, “How much did your life matter if no one close to you cares you died?” We are confident that readers will wonder who will claim them, and if the answer is not forthcoming, wonder what they can do to break through social isolation and repair broken relationships. We also hope that people will reach out to those they know to be at risk for going unclaimed, both individuals and high-risk populations. Do we really want to live in communities where more and more people go unclaimed?

This article, written by Elizabeth Kivowitz, originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.